What is Growth Mindset really?

‘Growth mindset’ is a recent buzzphrase. But what does it truly mean? And how can we use it to develop resilience and grit in youth?

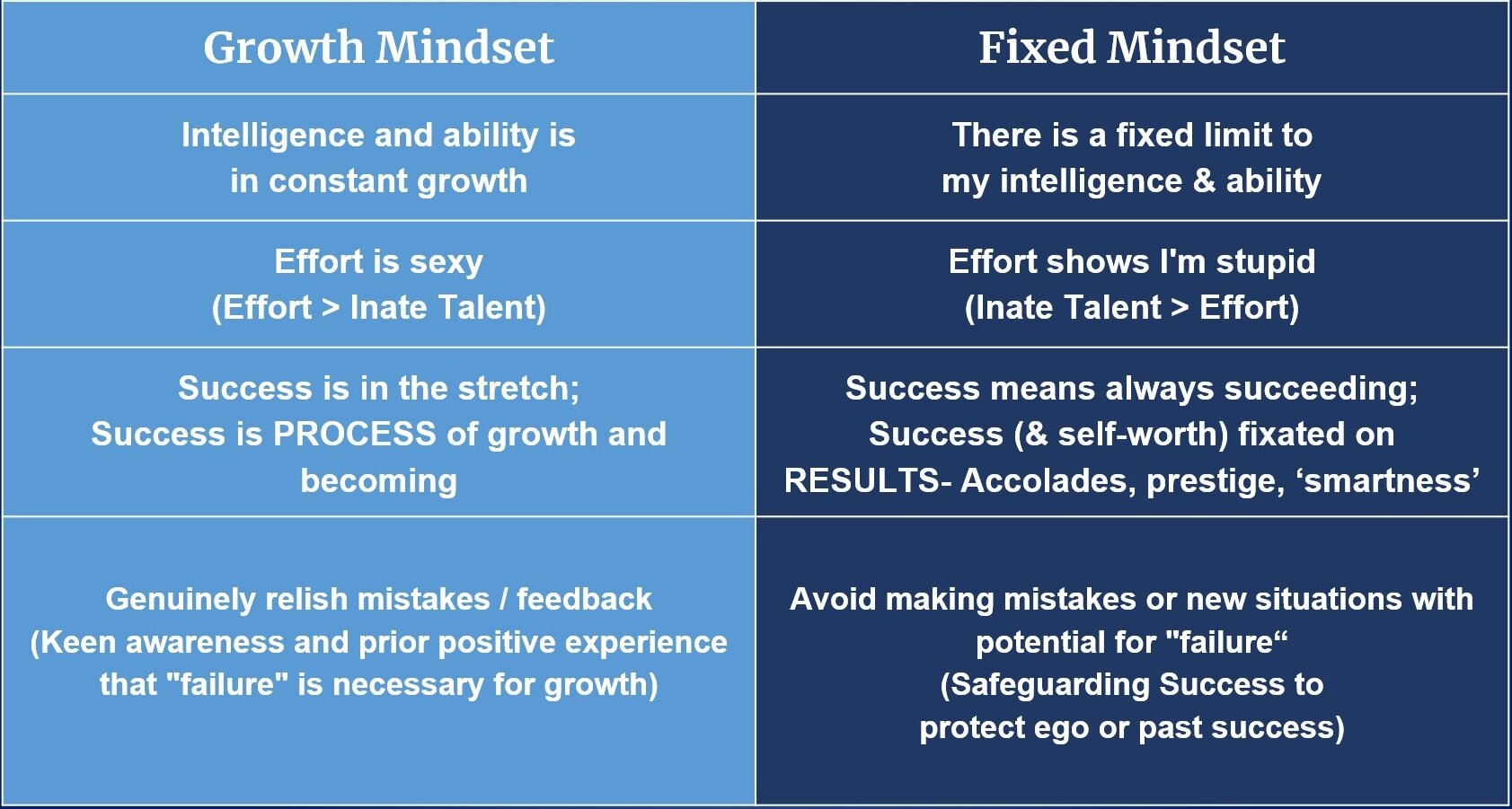

In short, the term is coined and made famous by Carol Dweck, a researcher passionate about helping others develop empowering ‘mindsets’. The ‘growth mindset’ is essentially a set of beliefs that inform 1. How people view themselves and 2. How they view effort and challenges. As such, our ‘mindset’ has a serious impact on our resilience and personal growth. The ‘growth mindset’ is opposed to the ‘fixed mindset’, and the differences are listed in the table below.

How can we cultivate a ‘growth mindset’? And does it really work?

I had an interesting conversation with a friend, who served as a trainee teacher in 2 separate primary schools - one with a clear focus on cultivating the ‘growth’ mindset, and one without.

She told me something fascinating – that she witnessed a clear difference in the speech pattern and the way kids responded to tough challenges and questions. In her words, it was “very obvious”.

As such, I do believe increasing awareness of the growth mindset in parents, educators and students, can really do tremendous good to raising our resilience as a society. Yet, the term is often quoted colloquially, and not given enough in depth treatment and focus.

As such, in this article, I will summarize 3 Groups of Studies that inform and support the growth mindset, and suggestions on how to use it to our advantage.

1. Studies on Neuroplasticity

Neuro-plastic-ity refers to the ‘plastic’ or changeable nature of the ‘neurons’ in our brain. In simple terms, our brain (and intelligence) is scientifically proven to ‘grow’ when we apply effort. How?

Neurons are special elongated cells in the brain responsible for carrying information, and ‘neural networks’ are a mass of neurons that interact with one another in our brains, as seen below:

In 1964, American neuroanatomist Dr. Marian Diamond found that an enriched environment (a cage with toys) produced changes in the rats’ cerebral cortex (a part of the brain responsible for thinking); their brains became heavier than the brains of the rats in a less stimulative environment.

Later studies and technology confirmed this concept of Neuroplasticity, that areas of the brain can grow or shrink with deliberate thinking patterns. For example, a study in 2000 showed that the London Taxi drivers had larger hippocampus (part of brain for spatial memory) compared to the non-drivers, and that the weight of the brain was positively correlated to the amount of time spent driving.

The video below shows an actual MRI imaging of how this process happens. When ‘thinking pathways’ are constantly activated, neurons grow and connect to one another in a process called myelination. When they are underused or abused (think drugs or accidents), they demyelinate (unjoin).

As such, this recent body of research forms the foundation of the ‘growth mindset’ - that anyone, kids and youth especially, can develop their ‘intelligence’ with deliberate effort and thinking.

What influences the amount and type of effort however, is largely dependent on one’s attitude and belief – hence the importance of the ‘growth mindset’.

2. Studies on talent VS hard work

Question: Would you rather be praised for talent or hard work? Which do you feel is more important to success? Chances are you picked hard work. However, is that what we really believe?

Many American surveys have asked this question, and hard work is quoted nearly 5 times as often. The results are consistent with a study done by a psychologist, Chia-Jung Tsay, who showed that musical experts rated ‘effortful training’ as more important than ‘natural talent’.

These experts were then asked to listen to a short clip of “different” individuals playing the piano. Unbeknownst to the subjects was that the same person was playing different parts of the same piece. In the separate descriptions, one person was described as a ‘striver’, while the other was described as a ‘natural’. The experts were then asked to pick who they felt would have a higher chance of success internationally. In direct contradiction to what they stated earlier, the subjects chose the ‘natural’.

This study underlies a key crippling bias that the musical experts (and many of us) have – we may logically say hard work is more important, but are emotionally attracted to ‘naturals’ or ‘talent’. This belief is further entrenched by the media, that glorifies and parades achievers as mythological one-of-a-kind superstars, and hardly every talk about the sweat behind achievement.

And yet, numerous research has shown that effort, specifically deliberate practice, is just as important, or even more crucial to achievement. Yes, talent plays a part, but its effort that triumphs it. Read the book ‘Talent is Overrated’ for a detailed argument of this. Or you can read a summary (click on summary).

So, what are the implications of favouring talent over effort? Here are a number of crucial ones:

1) Students get conditioned into a ‘fixed mindset’ and are not motivated to put in the hard work to ‘grow’ their brain.

2) Student use a “lack of talent” as an alibi or excuse for giving up. As Nietzsche said: “Our vanity promotes the cult of genius. For if we think of a ‘genius’ as someone magical, we are not obliged to compete and improve”. In other words, glorifying “talent” lets us off the hook of hard work.

3) As educators or parents, we favour talent and show it unconsciously through our verbal or non-verbal actions, especially in differing treatment of siblings or students. This reinforces the bias in students and further entrenches the ‘fixed mindset’

The last point especially, is linked to the final study, which also holds the key to understanding where a ‘fixed mindset’ originates and how to tackle it.

3. Carol Dweck’s’ landmark study on praising intelligence over effort in 11 year olds.

In 1998, Carol Dweck did a study that led to the eventual birth of the growth VS fixed mindset. She tested fifth graders (aged 10-11) on 10 IQ questions. The students excelled and received 3 different type of praise: Intelligence/ability (“you must be smart”), effort praise (“that’s a good score, you must’ve worked hard”), and a neutral result praise (that’s a good score).

Next, she gave the same kids a choice to try to a set of tougher questions. What she found was fascinating - the ability praised kids stuck to the previous easy problems. In contrast, 90% of the effort praised kids wanted tougher problems.

Eventually, she gave both groups of students tough questions. She found stark contrast in their attitudes and results as well. The ability praised one reported feeling more discouraged and frustrated, whereas the effort praised kids reported feeling more “fun”, satisfied and encouraged when they had to put in extra effort. They also did better than the counterparts while the control group (results praise) were in the middle.

And lastly, and perhaps most telling, is what happened after the test. When asked to write an anonymous letters to their peers, 40 per cent of the ability praised kids lied about their scores to inflate their intelligence.

This study was replicated several times with similar results. This underlies a key principle: by telling kids they are “smarter”, we could actually be making them feel dumber, act dumber, but claim they are smarter. In less crude terms, kids conditioned into this ‘fixed’ mindset have a greater fear of failure due to a perceived loss of respect or praise, or avoid challenges in order to protect an arbitrary sense of intelligence or success. This protective mechanism best represents the essence of the “fixed mindset” and how it cripples resilience.

How can parents or educators can build resilience and a growth mindset?

After getting a better understanding through these studies, here are some suggestions on building a ‘growth mindset’ and resilience in youth:

Change the belief that only outcomes matter. The desire to praise ability and intelligence stems partially from this belief. It’s the same reason why students who go to “better schools” are in danger of adopting the ‘fixed mindset’ and having their self-esteem dangerously fixed on external praise. Instead, value the process of growth, and recognize that effort can make one more intelligence and capable, as seen through the studies on neuroplasticity. Be conscious of verbal or non-verbal patterns that show favoritism to talent among students or siblings.

As parents or educators, reward and champion progress and effort, not just outcomes. A personal philosophy I share with students I train and coach is: “Never let success get to your head, or failure get to your heart”. We should not let kids get carried away and complacent with success. Rather, celebrate their progress, and ask “What’s next?”. In failure, guide them to independent thinking and emotional regulation through a simple 3 question reflection: “What happened? Why did it happen? And thus, what are the lessons I can learn/corrections I can make?”

If you’re a parent, allow you child room to try, fail and overcome. This is how the growth mindset is conditioned. Resilience is the ability to bounce back stronger from failure. Which means, experiencing failure is necessary to build resilience. Be there for them and guide them with overcoming the failure, but don’t overly protect them from it.

If you’re a student, how can you build a growth mindset?

Value your effort, and don’t use “lack of talent” as an excuse to slack

Convince yourself that your brain CAN grow with practice. Watch videos on neuroplasticity and read further to increase your belief.

See failures as exciting opportunities for growth, change and improvement, rather than potential sources of public humiliation. Stop caring too much about what other’s think, the last laugh will belong to you. Click here for 3 ways you can change your perspective to failure.

Seek discomfort and challenge. Don’t fear it. It is ONLY through challenge that we evolve to the next level – in our character, resilience, skills and maturity. If you don’t go through a challenge, you will never train your thinking nor emotional control. A good analogy is leveling up in a game – to complete new levels, you need better skills and thinking. Life is no different.

Conclusion

The ‘growth mindset’ is quite an exciting field of research which will have a greater emphasis in our education system in the coming years. Of course, these concepts are not new. Yet, the strength of it (and why it has gained international recognition) is the value of it being packaged and positioned as a programme and a “language” to cultivate resilience and champion the value of effort and progress. As such, if we can harness this “language” as educators or learners, and integrate it into curriculum, I do believe we will go a long way in raising the collective resilience of our youth!!!